‘New opportunities to democratize gene-edited crops and promote global sustainability’: Nature Biotechnology editors outline how small companies drive agricultural innovation

‘New opportunities to democratize gene-edited crops and promote global sustainability’: Nature Biotechnology editors outline how small companies drive agricultural innovation

CRISPR technologies offer new opportunities to democratize gene-edited crops and promote global sustainability.

The first CRISPR-edited food to enter the market, in 2020, was a tomato, the GABA-enriched Sicilian Rouge from Sanatech Seed. Del Monte has since grown pink pineapples that produce higher concentrations of lycopene and markets them for a mind-blowing $400.

The push for better traits can stretch beyond commercial cultivars of staple crops like maize and wheat, and instead focus on local crops and benefit farmers that grow them. Even with reduced regulation, however, it will still be a challenge to get those cis-edited crops to the people who would benefit most from the enhanced nutritional profiles and climate-tolerance traits.

A handful of companies are jumping at these opportunities. In 2021, the non-profit Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) launched a series of projects that are applying genome-editing technologies to plants important to the developing world, such as rice, cassava, sorghum and broccoli.

…

Another non-profit, Semilla Nueva, is working with researchers to produce biofortified corn, regarded as a cheap and productive crop in many lower- to middle-income countries, although it is limited in nutrients.

…

Gene-edited crops seem poised to step in and succeed where GM crops floundered. Free from regulatory obstruction and public disapproval, the power of agricultural biotech could be harnessed to better the planet and our own health. This will require collaboration between large seed companies and non-profits, governments and farmers, but it is important to think about long term, big-picture humanitarian goals, much as everybody loves the taste of a $400 pineapple.

This is an excerpt. Read the original post here

| Videos | More... |

Video: Nuclear energy will destroy us? Global warming is an existential threat? Chemicals are massacring bees? Donate to the Green Industrial Complex!

| Bees & Pollinators | More... |

GLP podcast: Science journalism is a mess. Here’s how to fix it

Mosquito massacre: Can we safely tackle malaria with a CRISPR gene drive?

Are we facing an ‘Insect Apocalypse’ caused by ‘intensive, industrial’ farming and agricultural chemicals? The media say yes; Science says ‘no’

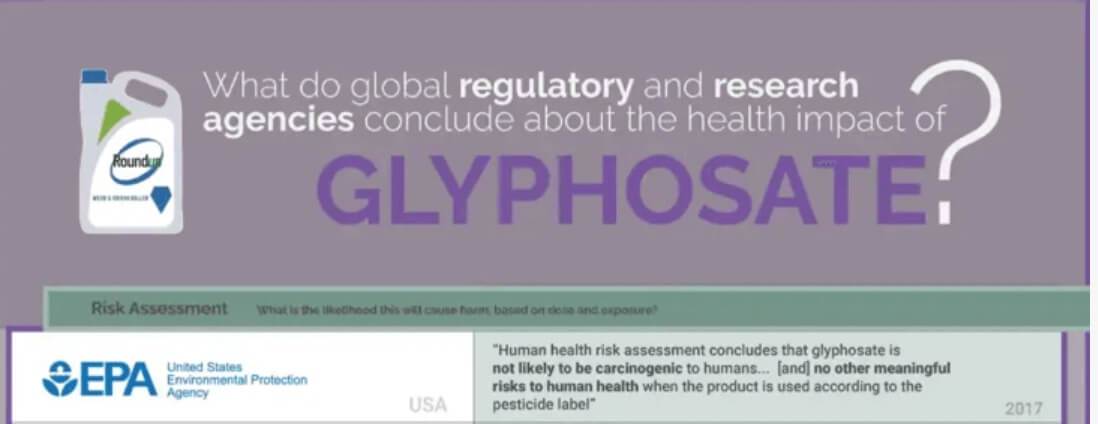

| Infographics | More... |

Infographic: Global regulatory and health research agencies on whether glyphosate causes cancer

| GMO FAQs | More... |

Why is there controversy over GMO foods but not GMO drugs?

How are GMOs labeled around the world?

How does genetic engineering differ from conventional breeding?

| GLP Profiles | More... |

Alex Jones: Right-wing conspiracy theorist stokes fear of GMOs, pesticides to sell ‘health supplements’

Viewpoint — Fact checking MAHA mythmakers: How wellness influencers and RFK, Jr. undermine American science and health

Viewpoint — Fact checking MAHA mythmakers: How wellness influencers and RFK, Jr. undermine American science and health Viewpoint: Video — Big Solar is gobbling up productive agricultural land and hurting farmers yet providing little energy or sustainabilty gains

Viewpoint: Video — Big Solar is gobbling up productive agricultural land and hurting farmers yet providing little energy or sustainabilty gains Fighting deforestation with CO2: Biotechnology breakthrough creates sustainable palm oil alternative for cosmetics

Fighting deforestation with CO2: Biotechnology breakthrough creates sustainable palm oil alternative for cosmetics Trust issues: What happens when therapists use ChatGPT?

Trust issues: What happens when therapists use ChatGPT? 30-year-old tomato line shows genetic resistance to devastating virus

30-year-old tomato line shows genetic resistance to devastating virus California, Washington, Oregon forge immunization alliance to safeguard vaccine access against federal undermining

California, Washington, Oregon forge immunization alliance to safeguard vaccine access against federal undermining The free-range chicken dilemma: Better for birds, but with substantial costs

The free-range chicken dilemma: Better for birds, but with substantial costs ‘You have to treat the brain first’: Rethinking chronic pain with Sanjay Gupta

‘You have to treat the brain first’: Rethinking chronic pain with Sanjay Gupta