Nobel Prize winner Emmanuelle Charpentier on why biotechnology-wary Europe should embrace plant gene editing

Nobel Prize winner Emmanuelle Charpentier on why biotechnology-wary Europe should embrace plant gene editing

Nobel Prize winner for Chemistry Emmanuelle Charpentier speaks. The authoritative opinion of the French biochemist and geneticist who received an honorary degree from the University of Bologna

“There is enormous potential in this tool that concerns us all. Not only has it revolutionized basic science, but it has enabled innovative crops and will lead to new cutting-edge medical treatments.” These were the motivations of Claes Gustafsson, head of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry in 2020, for awarding the prize to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, two researchers who developed the Crispr/Cas9 technique, the “molecular scissors” that revolutionized genome editing, transforming it into a rapid and economical procedure, paving the way for [Assisted Evolution Techniques].

Emmanuelle Charpentier was recently awarded an honorary degree by the University of Bologna, on which occasion we had the privilege of meeting her to ask her a few questions.

Many people think that GMOs and organisms obtained through [Assisted Evolution Techniques] are the same thing. What is your point of view?

“It’s a question of terminology, let’s put it this way. If you are a biologist or a geneticist, you could argue that plants in nature are genetically modified organisms. Because they genetically modify themselves every minute and the whole genome is constantly mutating. Now, the term GMO is used for plants that have been genetically modified artificially by humans, using technologies that introduce foreign DNA, after which many other terminologies have been followed, but I think that ordinary people are not aware that natural genetic improvement leads to plants that are also genetically modified, often even more modified than GMOs obtained by humans.

In fact, when you intervene on plants with traditional genetic improvement, many DNA sequences get mixed up, so that in the end you end up with a genome that is very different from the original, while a biologist with Crispr does something very specific and knows exactly what has been mutated. Fifty or sixty years ago we couldn’t sequence the entire genome of the plant, but today we can, and above all it is possible to verify the precision of the technology. Precisely this genetic precision could generate a plant exactly in the way it could happen in nature.

If well explained, I think that ordinary people will understand that it is a positive technology, that would allow, without the introduction of foreign DNA, to develop plants that can resist, for example, the climate changes that we will increasingly have to face in the future. In short, I think that people are in favor of this technology”.

This is the point: how can we explain to ordinary people in simple and understandable language that [Assisted Evolution Techniques]s are not a “bad” technology?

“You should find an analogy with something they can understand, an example they can refer to of something that is modified by adding a foreign piece and something that is modified without introducing a foreign piece, which shows that it is different in a certain sense, even if what they think is that it is the same thing. I don’t have an analogy in mind at the moment, but I know that in Italy you can’t grow GMOs, but animals are raised with feed obtained also from GMO plants imported from abroad (South America, Spain…) and this is a contradiction. A couple of years ago, speaking with the head of the largest farmers’ association in France, he told me that farmers are open to this new technology.

If I’m not mistaken, for decades, if not centuries, they themselves have been geneticists, doing genetic improvement without knowing it, and now they have a problem if they have to do it in the laboratory, because they certainly can’t have a laboratory and therefore they would have to contract out the work. The problem is more in the regulation in Europe and in the economic aspect of the issue, because there is a patent and therefore there are people who make money from it, while you would simply like the farmers to make money from it. We biologists think about the plants that they would like to grow and they have it available for free. Maybe it’s a bit naive or simplistic as a reasoning, but it’s my point of view”.

Do you think these new techniques are particularly useful for organic farming?

“An organic farmer could, as we did in the past, improve plants and have an interest in this technology, for example, to reproduce species that existed in the past. Not because one has to produce things from the past, but because it is something that adapts better to the soil, to the environment, and therefore allows one to make plants “tailor-made” for that specific site, for that specific climate. When I worked on it, I actually thought that this technology would be used in medicine for operations tailored to certain types of diseases, in short personalized, even if I don’t know if that’s the right word.”

Does this new technology have any limitations?

“Yes, it has limitations in the sense that sometimes you would like to modify a certain site or a certain letter of the DNA code and it is not possible to do so, because this technology has limitations in its intrinsic way of being, so perhaps you would like to change some letters, but as versatile as the tool is you cannot. Let’s say that this has to do with genetics, in the sense that sometimes there is a site in the DNA that cannot be easily modified because it is a trait that has a certain structure that is refractory to any change (and would also be refractory to a change made through traditional genetic improvement), in short there are always limits to genetic technology.

The great benefit I see in any technology today is that at the end of the process you can verify what has been modified, at least at the DNA level, because you can sequence the entire genome of the plant, read it and know exactly what has been changed. I am not a plant biologist, but as I said plants are constantly modifying their genome, that is what plants are and what is natural is natural. The word natural is under the understanding that there are also natural genetic modifications that are constantly occurring, that is the point. And regulation should be done according to the technology, not the other way around, although it is obvious that technology can be used well or badly.

[Editor’s note: This article has been translated from Italian.]

Read the original post here

| Videos | More... |

Video: Nuclear energy will destroy us? Global warming is an existential threat? Chemicals are massacring bees? Donate to the Green Industrial Complex!

| Bees & Pollinators | More... |

GLP podcast: Science journalism is a mess. Here’s how to fix it

Mosquito massacre: Can we safely tackle malaria with a CRISPR gene drive?

Are we facing an ‘Insect Apocalypse’ caused by ‘intensive, industrial’ farming and agricultural chemicals? The media say yes; Science says ‘no’

| Infographics | More... |

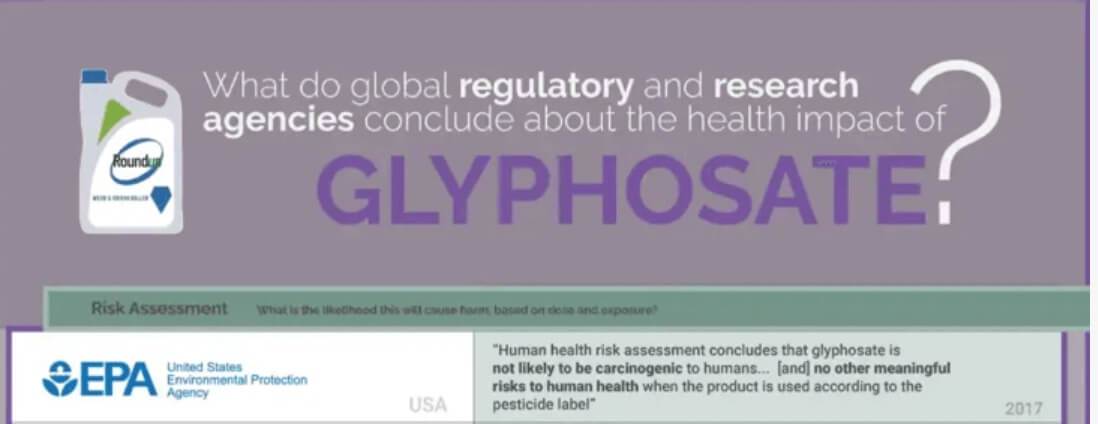

Infographic: Global regulatory and health research agencies on whether glyphosate causes cancer

| GMO FAQs | More... |

Why is there controversy over GMO foods but not GMO drugs?

How are GMOs labeled around the world?

How does genetic engineering differ from conventional breeding?

| GLP Profiles | More... |

Alex Jones: Right-wing conspiracy theorist stokes fear of GMOs, pesticides to sell ‘health supplements’

Viewpoint — Fact checking MAHA mythmakers: How wellness influencers and RFK, Jr. undermine American science and health

Viewpoint — Fact checking MAHA mythmakers: How wellness influencers and RFK, Jr. undermine American science and health Viewpoint: Video — Big Solar is gobbling up productive agricultural land and hurting farmers yet providing little energy or sustainabilty gains

Viewpoint: Video — Big Solar is gobbling up productive agricultural land and hurting farmers yet providing little energy or sustainabilty gains Fighting deforestation with CO2: Biotechnology breakthrough creates sustainable palm oil alternative for cosmetics

Fighting deforestation with CO2: Biotechnology breakthrough creates sustainable palm oil alternative for cosmetics Trust issues: What happens when therapists use ChatGPT?

Trust issues: What happens when therapists use ChatGPT? 30-year-old tomato line shows genetic resistance to devastating virus

30-year-old tomato line shows genetic resistance to devastating virus California, Washington, Oregon forge immunization alliance to safeguard vaccine access against federal undermining

California, Washington, Oregon forge immunization alliance to safeguard vaccine access against federal undermining The free-range chicken dilemma: Better for birds, but with substantial costs

The free-range chicken dilemma: Better for birds, but with substantial costs ‘You have to treat the brain first’: Rethinking chronic pain with Sanjay Gupta

‘You have to treat the brain first’: Rethinking chronic pain with Sanjay Gupta