Viewpoint: Here’s why almost all international agricultural biotechnology regulatory structures are a scientific mess, and what reforms are needed

Viewpoint: Here’s why almost all international agricultural biotechnology regulatory structures are a scientific mess, and what reforms are needed

The 1975 Asilomar Conference established risk-appropriate, evidence-based regulations for biotechnology.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety is a risk-inappropriate, precaution-based regulatory framework that is a significant barrier to biotechnological innovation.

There is now a global scientific consensus on the safety of agricultural biotechnology products. Major agricultural biotechnology–producing countries have not adopted the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety.

The lack of agricultural biotechnology innovation adoption in some countries

raises the risks of food insecurity.

For the full potential of scientific innovations to be realized by society, efficient regulation is crucial. This is especially the case if science is to make meaningful contributions to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals or the Paris Accord greenhouse gas emission reductions. It defies common sense to invest public research money in the development of new products and technologies to then only achieve one-third of their potential, as has been the case with GM crops [37]. This marginal level of benefit clearly illustrates an important repercussion of the global regulatory failure of agbiotech regulation (see Outstanding questions).

Efficient regulations rely on empirically based risk assessment methodologies and robust data to undertake risk-appropriate assessment of innovative products and technologies. Parallel to this is a variety approval decision-making process that makes decisions on the basis of scientific risk assessment and that has not become a politicized process that often functions as a mechanism to ban and/or delay all innovative and seemingly deemed safe GM products, regardless of their value to society. Some countries have implemented evidence-based risk assessment regulatory frameworks but have politicized variety approval processes that have banned the commercial production of GM crops for over 20 years.

More important, in the context of food insecurity, countries that grapple with food insecurity are increasingly turning to agbiotech as a contributor to resolving their food insecurity and climate change challenges. Such countries have taken a pragmatic approach where, even though they are CPB parties and thus mandated to comply with its requirements, they have developed and deployed pragmatic approaches including feasible and functional biosafety systems.

GM cowpea was commercialized in Nigeria in 2019 and has recently been approved in Ghana. In 2022, Kenya lifted its 10-year ban on the production of GM crops, facilitating the commercialization of GM corn. Numerous other countries that had previously expressed opposition to GM crop technology are making public announcements reversing previous policies and removing barriers regarding GM crop adoption. Honduras, a country with limited R&D capacities and a CPB party, developed and implemented a functional biosafety regulatory system that allowed crop and trait technologies valuable to the country to proceed after the proper biosafety evaluations. However, as discussed in the preceding text, inappropriate regulation will slow the achievement of benefits from GM crop adoption. Such countries will need to find a regulatory approach that enables the knowledge and experience gained since Asilomar to better facilitate innovation adoption.

With many international climate and environment agreements having 2030 as a target achievement date, there is a significant potential that many targets will not be reached, in large part because of inappropriate regulations. A fundamental underlying premise of science is that it builds on previous knowledge and experience. However, as many precautionary-based regulatory systems demonstrate, in many jurisdictions, virtually no lessons have been taken from the knowledge or experience gained since the development of the first rDNA guidelines 50 years ago. For innovation to reach its full potential, the knowledge of 50 years of safe agbiotech research and commercialization needs to be recognized and respected. Failure to do so risks unnecessary food insecurity and poverty.

This is an excerpt. Read the original post here

| Videos | More... |

Video: Nuclear energy will destroy us? Global warming is an existential threat? Chemicals are massacring bees? Donate to the Green Industrial Complex!

| Bees & Pollinators | More... |

GLP podcast: Science journalism is a mess. Here’s how to fix it

Mosquito massacre: Can we safely tackle malaria with a CRISPR gene drive?

Are we facing an ‘Insect Apocalypse’ caused by ‘intensive, industrial’ farming and agricultural chemicals? The media say yes; Science says ‘no’

| Infographics | More... |

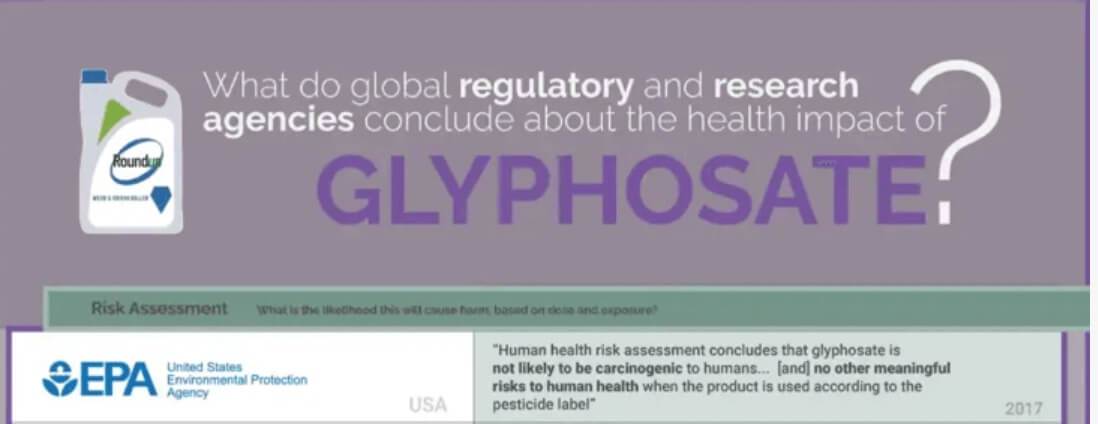

Infographic: Global regulatory and health research agencies on whether glyphosate causes cancer

| GMO FAQs | More... |

Why is there controversy over GMO foods but not GMO drugs?

How are GMOs labeled around the world?

How does genetic engineering differ from conventional breeding?

| GLP Profiles | More... |

Alex Jones: Right-wing conspiracy theorist stokes fear of GMOs, pesticides to sell ‘health supplements’

A single high dose of LSD can ease anxiety and depression for months

A single high dose of LSD can ease anxiety and depression for months From plastic coasters to human hearts: Inside the race to print the human body

From plastic coasters to human hearts: Inside the race to print the human body CRISPR pork: U.S. approves first gene-edited pigs for consumption

CRISPR pork: U.S. approves first gene-edited pigs for consumption ‘SuperAgers’: Why some people have the brains and memory capacity of people decades younger

‘SuperAgers’: Why some people have the brains and memory capacity of people decades younger  From ‘Frankenfood’ to superfood: Can the purple tomato overcome GMO myths to win over consumers?

From ‘Frankenfood’ to superfood: Can the purple tomato overcome GMO myths to win over consumers? Baby food panic, brought to you by trial lawyers hoping to prosecute by press release

Baby food panic, brought to you by trial lawyers hoping to prosecute by press release Viewpoint: Life and death decisions: RFK, Jr.’s shady FDA “expert panels” operate in secret with no transcripts or conflict of interest reviews

Viewpoint: Life and death decisions: RFK, Jr.’s shady FDA “expert panels” operate in secret with no transcripts or conflict of interest reviews When farmers deny science: The hypocrisy hurting agriculture’s credibility

When farmers deny science: The hypocrisy hurting agriculture’s credibility